Himachal Pradesh Revives Lottery to Tackle Rs 1 Lakh Crore Debt Crisis

Sep, 23 2025

Sep, 23 2025

Financial Pressure Sparks Lottery Revival

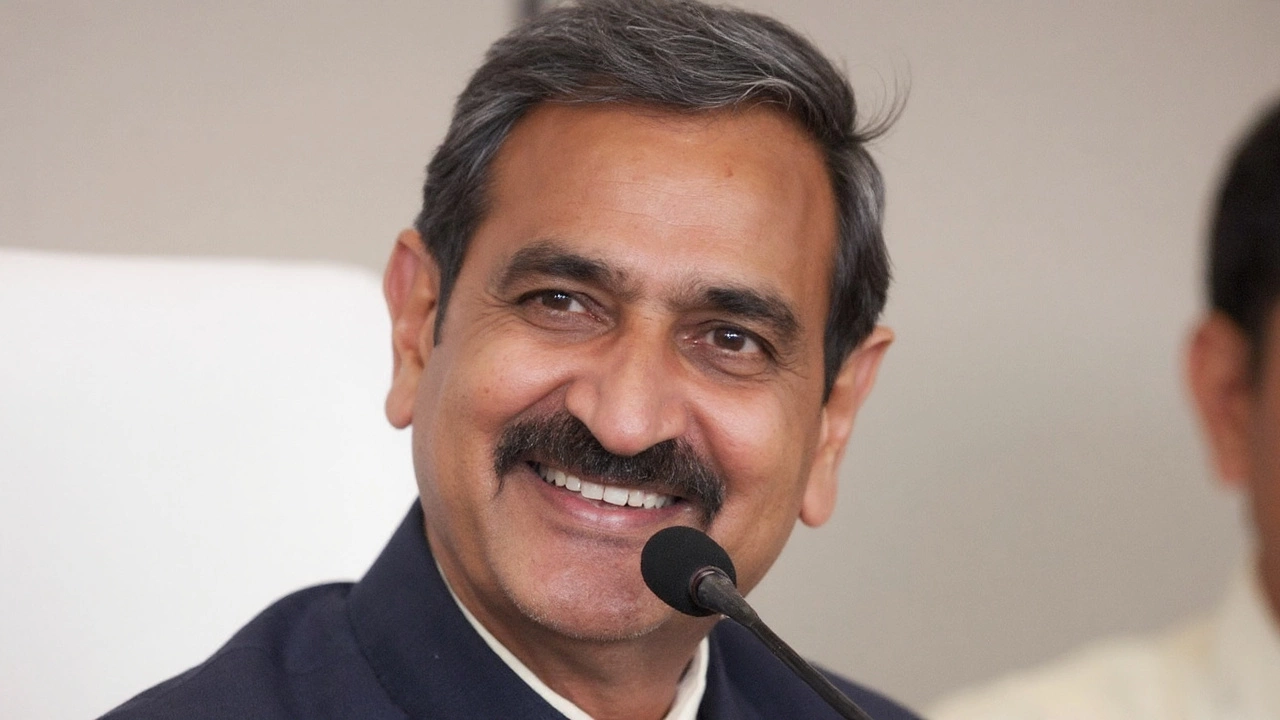

Himachal Pradesh is at a crossroads. The hill state’s balance sheet has swelled to over Himachal Pradesh lottery‑driven expectations, with debt levels topping Rs 1 lakh crore. With central transfers drying up and GST compensation gone, the finance team, led by Deputy Chief Minister Mukesh Agnihotri, started hunting for any legal revenue stream that could plug the fiscal gap. Their answer? Bring back the state‑run lottery, but this time as a fully digitised, tightly monitored system.

The idea resurfaced in the cabinet meeting of July 2025, where Chief Minister Sukhvinder Singh Sukhu gave the green light after the Resource Mobilisation Committee presented a glossy revenue projection: Rs 50‑100 crore a year. That figure may sound modest against a trillion‑rupee debt, but it is comparable to what smaller states earn from similar schemes. For context, Kerala – the country’s lottery powerhouse – clocked over Rs 13,582 crore last financial year, while Punjab managed Rs 235 crore and the tiny state of Sikkim pulled in roughly Rs 30 crore.

Himachal’s lottery was originally shelved in 1996 and officially banned in 1999 under then‑CM Prem Kumar Dhumal, citing rampant losses suffered by ticket‑buyers and legal provisions under the Lotteries (Regulation) Act, 1998. The ban was specifically encoded in Sections 7, 8 and 9 of the act, driven by concerns that unregulated gambling was harming citizens. Fast forward three decades, and the government argues that a state‑controlled, digitised platform can avoid the pitfalls of the past while adding a new line to the exchequer.

Political Pushback and Implementation Plans

The decision has sparked a familiar political tug‑of‑war. The BJP, now the opposition in Himachal, has pounced on the move, with former CM Dhumal warning of “social harm” and a repeat of the exploitative practices that led to the original ban. He and other BJP leaders claim the revival contradicts the very reasons the lottery was scrapped.

Congress leaders, on the other hand, have dismissed the criticism as double standards, pointing out that lotteries continue to thrive in several BJP‑led states, including Goa, Maharashtra and West Bengal. Technical Education Minister Rajesh Dharmani reminded critics that the central government has no jurisdiction over private betting platforms that often bleed money from unwary players. A state‑run lottery, he argued, would be a transparent, accountable alternative that actually nets revenue for public services.

Media adviser Naresh Chauhan echoed this sentiment, insisting the upcoming lottery will run on a secure digital interface, with real‑time monitoring to curb fraud. The plan mirrors Punjab’s model, which features weekly, monthly and special festival draws, all overseen by a dedicated regulatory cell. Himachal intends to adopt similar operational safeguards, ensuring every ticket sold is traceable and every prize payout is recorded.

Beyond the political discourse, the finance department has laid out a concrete rollout roadmap. A presentation to the cabinet outlined the following steps:

- Finalize the digital platform architecture, partnering with a certified fintech provider.

- Set up a state lottery authority to issue licenses, monitor sales and audit prize disbursements.

- Launch a public awareness campaign that stresses responsible participation.

- Begin with low‑stakes tickets to gauge market response, then expand to higher‑value draws.

Thirteen Indian states currently operate lotteries, ranging from the high‑earning Kerala to the nascent setups in the North‑Eastern region. Himachal’s entry into this club places it alongside states that have turned lottery proceeds into funding for health, education and infrastructure projects.

Economists point out that while the lottery alone won’t erase the massive debt, it provides a modest, recurring cash inflow that can be earmarked for specific line items—perhaps subsidising flood‑relief initiatives or bolstering the state’s tourism marketing budget. The state has already been scouting other revenue avenues, such as expanding mineral leases, leveraging hydro‑electric potential and promoting adventure tourism, but the lottery offers an immediate, low‑cost solution.

Critics, however, caution that any gamble‑like activity carries a social cost, especially in rural pockets where disposable income is thin. They urge the government to pair the lottery launch with financial‑literacy drives and robust grievance redressal mechanisms. The success of the venture will likely hinge on how well the administration balances revenue ambition with consumer protection.

As of now, the Himachal government has not set a definitive launch date. Officials assure the public that the digital framework will be tested extensively before tickets hit the market. If the gamble pays off, the state could see a steady infusion of cash, easing the pressure on its beleaguered finances while avoiding the pitfalls that led to the lottery’s original demise.